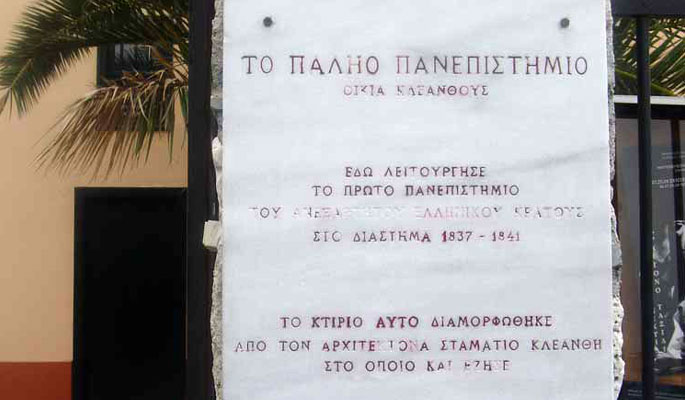

Kleanthi-Schaubert, or the “Old University,” is on Tholou street in one of the higher sections of Plaka. Built around the 17th Century, the institution was purchased from its Ottoman owner by two close friends, architects Kleanthis and Schaubert, who, after arriving in the newly liberated Athens, went to work on the old building, repairing and restoring its huge walls and domed basements, adding other buildings, and uniting them all into a single complex. In 1834 the building housed the Girls High School and, later, the newly founded University.

Kleanthi-Schaubert, or the “Old University,” is on Tholou street in one of the higher sections of Plaka. Built around the 17th Century, the institution was purchased from its Ottoman owner by two close friends, architects Kleanthis and Schaubert, who, after arriving in the newly liberated Athens, went to work on the old building, repairing and restoring its huge walls and domed basements, adding other buildings, and uniting them all into a single complex. In 1834 the building housed the Girls High School and, later, the newly founded University.

Then, in 1837, three new rooms and an Anatomy auditorium were added to cover the needs of the new University. When the University finally moved into its own building after 1841, the original Kleanthi Residence became the Didaskaleion and the Experimental InterTeaching School, which was later used as a barracks. The facility changed hands many times over the years, and was used for various purposes until 1963 when it was declared a listed building. In 1967 it was officially assigned to the University. Since then it has been restored, and now houses the University’s History Museum.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

The 17th century Church of Agioi Anargyroi, also known as the Metochion of the Holy Sepulchre, is located at the Anafiotika, in Plaka. Originally opened as a convent, presumed to have been owned by the prominent Kolokinthi family.

The church is a single-clite basilica, dedicated to the Ag. Anargyroi. Due to its function as an embassy church of the Holy Sepulchre since the 18th century, the Metochion is deeply involved with the holy ceremonies of Easter. Designated as the point of initial reception of the Holy Light from the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, on the night of celebration of the Holy Resurrection, the church attracts many visitors. It was built on the site of an ancient temple dedicated to goddess Aphrodite.

The church is a single-clite basilica, dedicated to the Ag. Anargyroi. Due to its function as an embassy church of the Holy Sepulchre since the 18th century, the Metochion is deeply involved with the holy ceremonies of Easter. Designated as the point of initial reception of the Holy Light from the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, on the night of celebration of the Holy Resurrection, the church attracts many visitors. It was built on the site of an ancient temple dedicated to goddess Aphrodite.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

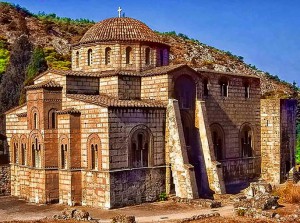

The church of Agios Nikolaos Ragavas is located in Plaka, close to the Anafiotika neighborhood. Built in the 11th century, it is one of the major monuments from that era. Based on the simple four-aisled, cross-in-square design, the church is topped with a small octagonal dome of the Athenian era. Originally belonging to a Byzantine family named Ragavis.

The church of Agios Nikolaos Ragavas is located in Plaka, close to the Anafiotika neighborhood. Built in the 11th century, it is one of the major monuments from that era. Based on the simple four-aisled, cross-in-square design, the church is topped with a small octagonal dome of the Athenian era. Originally belonging to a Byzantine family named Ragavis.

The church became derelict during the Revolution of 1821, but was eventually rebuilt using the original materials. Since then, it has undergone numerous modifications, which have significantly altered its appearance. During the 1970’s it was partially restored to its original condition, but not completely. Tradition has it that this church’s bell was the first one to ring out following the liberation of Athens from German occupation on October 12, 1944.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

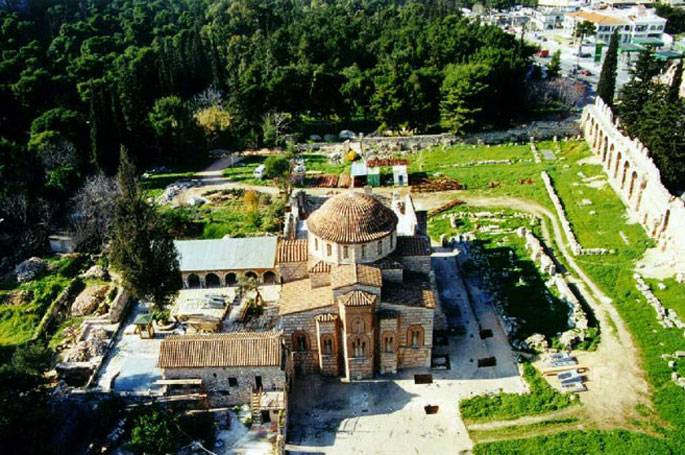

Situated at the edge of the Haidari parkland, the Dafni Monastery is said to have been built at the site of the ancient temple of Apollo Dafnaios. Fortified and surrounded by high defensive walls, only two entrances lead to the perivolos, where the Monastery’s main church is located, the imposing “Katholikon.”

Situated at the edge of the Haidari parkland, the Dafni Monastery is said to have been built at the site of the ancient temple of Apollo Dafnaios. Fortified and surrounded by high defensive walls, only two entrances lead to the perivolos, where the Monastery’s main church is located, the imposing “Katholikon.”

Other structures, including the monks’ chambers and the dining room, are also located here. Like most of Athens’ Byzantine buildings, the monastery’s Katholikon dates from the 11th Century, and has been restored multiple times during its thousand years of existence. Fortunately, many of its exquisite, original mosaic decorations have been preserved.

Over the centuries, the Monastery gradually fell into disrepair and, by the late 19th Century, it had been abandoned by the monks, subsequently being used as a public mental hospital. Today, however, this fortified monastery is included in the Unesco World Record of Cultural Heritage.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

The Herod Atticus Odeon, or the Irodeion as it is called today, was built on the south-western slope of the rock of the Acropolis during the Roman era, by the Athenian magnate Herod Atticus, in memory of his wife Regilla. Following the city’s decline during the Byzantine era, the Odeon became a derelict and was buried under tons of dirt. During the subsequent Ottoman occupation, foreign visitors to the site gave the scant remnants many different names, most of them made up. It seemed as if the Irodeion would simply fade from memory.

The Herod Atticus Odeon, or the Irodeion as it is called today, was built on the south-western slope of the rock of the Acropolis during the Roman era, by the Athenian magnate Herod Atticus, in memory of his wife Regilla. Following the city’s decline during the Byzantine era, the Odeon became a derelict and was buried under tons of dirt. During the subsequent Ottoman occupation, foreign visitors to the site gave the scant remnants many different names, most of them made up. It seemed as if the Irodeion would simply fade from memory.

That is, until 1764, when British archaeologist, Chandler, reawakened interest in Herod Atticus Odeon. Then, in the 19th Century, excavations unearthed the ruins of the ancient theatre. Completely refurbished by the 1950s, the seats were now covered with Pentelic marble, and the orchestra with marble from Mt Hymettus. Since then the theatre has been used for high-level cultural productions during the summer season, mainly the Athens Festival.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

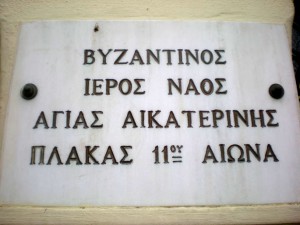

Located in Plaka, the Church of Ag. Aikaterini was built in the middle of the 11th Century, and is a domed, cross-in-quare, four-aisled complex. Experts of Byzantine history believe the church was dedicated to Ag. Theodoros, as indicated by the inscription on the marble column supporting the Altar.

Located in Plaka, the Church of Ag. Aikaterini was built in the middle of the 11th Century, and is a domed, cross-in-quare, four-aisled complex. Experts of Byzantine history believe the church was dedicated to Ag. Theodoros, as indicated by the inscription on the marble column supporting the Altar.

This is the old parish church of the Alikokos neighbourhood in Plaka, just opposite the choragic monument of Lysicrates, which, in later years was enclosed by the old Catholic Capuchin monastery. Its interior murals were painted in the late 19th Century by hagiographer, G.D. Kafetzidakis.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

On Areos street, just opposite the entrance to the Monastiraki metro station, lies the archaeological site of Hadrian’s Library. Though only a few remnants remain intact, many other valuable findings are being unearthed in this ongoing excavation. Described in written detail by Pausanias the traveller in the 2nd century A.C., the Library was comprised of 100 columns, supporting a gilded roof, and was decorated with precious alabaster artifacts.

On Areos street, just opposite the entrance to the Monastiraki metro station, lies the archaeological site of Hadrian’s Library. Though only a few remnants remain intact, many other valuable findings are being unearthed in this ongoing excavation. Described in written detail by Pausanias the traveller in the 2nd century A.C., the Library was comprised of 100 columns, supporting a gilded roof, and was decorated with precious alabaster artifacts.

Today the visitor can see the pediments of the internal yard columns, the four, seven-meter-long forming alleys, the foundations, some two-story walls near the southern perimeter, remnants of a pavilion in the centre of the yard, and, to the north-west, the Library entrance, framed by seven Corinthian era columns. The entrance to the site is on Areos street., opposite the exit of the Monastiraki Metro station.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

Philhellene Roman Emperor, Hadrian (117-138 μ.Χ.), founded a new neighbourhood near the eastern border of ancient Athens. To honour him, the Athenians named it Adrianopolis, and in 131-132 A.C., built an arch of Pentelic marble, leading from the old city into the new. Situated near the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the arch remains intact and in excellent condition, and is one of the most recognizable, and photographed landmarks of the city.

Philhellene Roman Emperor, Hadrian (117-138 μ.Χ.), founded a new neighbourhood near the eastern border of ancient Athens. To honour him, the Athenians named it Adrianopolis, and in 131-132 A.C., built an arch of Pentelic marble, leading from the old city into the new. Situated near the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the arch remains intact and in excellent condition, and is one of the most recognizable, and photographed landmarks of the city.

In the late 18th century, the arch served as part of the city’s defensive wall, known at the time as the Haseki wall. It was later named the “Gate of the Princess” or the “Arch Gate.” Today it stands in the very heart of modern Athens, a stunning marble monument to the days of glory in ancient Athens.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

Visible to the southwest of the Acropolis, is the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Construction began in the 6th century B.C., during the rule of the tyrant of Athens, Peisistratus. But construction was halted throughout the era of the Athenian Democracy, as the temple was deemed a symbol of tyranny. Later, during the Hellenistic period, there was an attempt to resume construction, by Antiochus IV Epiphanes, King of Syria, but work was once again terminated when he died. Still only half-finished, serious damage was inflicted on the Temple by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who sacked of Athens in 86 B.C.

It was not until the accession of the Philhellene Emperor, Hadrian, in 131 A.C. that the project was finally completed, following its original design. The Temple was abandoned and badly damaged again, during the Herulian sack of Athens in the 3rd century, when most of the columns were torn down, to be used as building materials. Sixteen columns remain today, fifteen of them still standing and one lying on the ground, where it fell during a storm in 1852. Apart from the main temple, the site also contains remnants from Roman thermae, Classical era residences, foundations of an Early Christian basilica, and parts of the city’s Roman fortifications.

It was not until the accession of the Philhellene Emperor, Hadrian, in 131 A.C. that the project was finally completed, following its original design. The Temple was abandoned and badly damaged again, during the Herulian sack of Athens in the 3rd century, when most of the columns were torn down, to be used as building materials. Sixteen columns remain today, fifteen of them still standing and one lying on the ground, where it fell during a storm in 1852. Apart from the main temple, the site also contains remnants from Roman thermae, Classical era residences, foundations of an Early Christian basilica, and parts of the city’s Roman fortifications.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

The impressive Stoa of Attalos, is the restored building located on the eastern side of the Ancient Agora. Now protected as part of the archaeological site, the stoa was named after King Attalus II of Pergamon, who gave it to the city as a gift. Erected over a span of twenty-one years, between 159 and 138 B.C., the stoa was, at the time, the longest free-standing, roofed building in the city. Built to house the city’s commercial activities, the two-story structure was 120 meters long, with 21 stores and workshops.

The impressive Stoa of Attalos, is the restored building located on the eastern side of the Ancient Agora. Now protected as part of the archaeological site, the stoa was named after King Attalus II of Pergamon, who gave it to the city as a gift. Erected over a span of twenty-one years, between 159 and 138 B.C., the stoa was, at the time, the longest free-standing, roofed building in the city. Built to house the city’s commercial activities, the two-story structure was 120 meters long, with 21 stores and workshops.

With walls constructed entirely of limestone, the doorjambs, doors, staircases, columns and wall studs were all made of white Pentelic marble. Destroyed during the Herulian sack of Athens in 267 A.C., the Stoa’s remnants were later used to build the Late Roman fortification wall. Rebuilt in the 1950s by the American Archaeological Institute, the Stoa rose again, this time to house the Museum of the Ancient Agora.

Source: www.athensattica.gr