In the Classical era, the Theatre of Dionysus was where Attican drama was taught during the celebration of the Great Dionyssia, one of the major religious festivals of the city. The theatre formed a substantial part of the temple of Dionysus Elephtherios, located below the rock of the Acropolis. Believed to have been built during the rule of the descendants of the tyrant Peisistratus, it underwent so many subsequent alterations and expansions, it became impossible to follow its precise architectural evolution.

In the Classical era, the Theatre of Dionysus was where Attican drama was taught during the celebration of the Great Dionyssia, one of the major religious festivals of the city. The theatre formed a substantial part of the temple of Dionysus Elephtherios, located below the rock of the Acropolis. Believed to have been built during the rule of the descendants of the tyrant Peisistratus, it underwent so many subsequent alterations and expansions, it became impossible to follow its precise architectural evolution.

Today’s remnants derive from the late Roman phase of the Theatre, with only a few rows of benches remaining from its Classical phase. Currently, an effort is underway to restore the ancient theatre, using the original Corinthian stone fragments that are scattered over the site.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

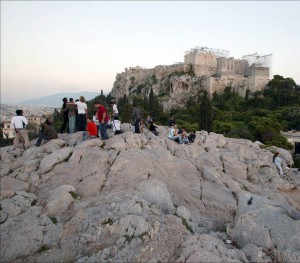

The ancient Athenian Supreme Court once occupied this rocky hill just northwest of the Acropolis. Judging cases from murder and arson to sacrilege, the court even made decisions on new religious ideas.

The ancient Athenian Supreme Court once occupied this rocky hill just northwest of the Acropolis. Judging cases from murder and arson to sacrilege, the court even made decisions on new religious ideas.

It is believed that this location got its name from one of two sources, the first being the murder trial of the god, Ares who, according to mythology, was tried on this very spot by Kekrops, King of Athens, for the murder of Allerothios, son of Poseidon. The second theory is that it came from the temple of the Areian Erinyes, the sinister deities of punishment, scruples, and revenge. Mythology also tells us that the Areopagus also convicted Orestes for the killing of his mother Clytemnestra, and was saved by the vote of goddess Athena. The Athenians then referred to the Erinyea as being humble and pacified.

From the Mycenaean era until the Geometrical years (1600-700 B.C.), the northern slope of the hill was used as a cemetery. Subsequently, during the late Roman era from the 4th to 6th century A.C., four mansions were built on the Areopagus, replaced in the 15th and 16th Centuries by a church honouring Saint Dionysius Aeropagite, the first Christian bishop of Athens.

From the Mycenaean era until the Geometrical years (1600-700 B.C.), the northern slope of the hill was used as a cemetery. Subsequently, during the late Roman era from the 4th to 6th century A.C., four mansions were built on the Areopagus, replaced in the 15th and 16th Centuries by a church honouring Saint Dionysius Aeropagite, the first Christian bishop of Athens.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

At the western side of the Acropolis, located between “Mousseion (Philopappos) Hill”, and the observatory, Hill of the Nymphs, lies the rock of the Pnyx. Due to its unique morphology and size, it was selected as the “seat” of the Ecclesia, and the area of assembly for Athenian citizens. It is believed that official functions at the Pnyx began sometime in the 6th Century, during the age of the Reforms of Cleisthenes (508 B.C.).

At the western side of the Acropolis, located between “Mousseion (Philopappos) Hill”, and the observatory, Hill of the Nymphs, lies the rock of the Pnyx. Due to its unique morphology and size, it was selected as the “seat” of the Ecclesia, and the area of assembly for Athenian citizens. It is believed that official functions at the Pnyx began sometime in the 6th Century, during the age of the Reforms of Cleisthenes (508 B.C.).

The first archaeological findings here date from the 5th century B.C. In The New Testament, the Acts of the Apostles mention Apostle Paul’s Homily to the Athenians on the Pnyx in 51 A.C., which introduced the Christian religion to the Greeks. Thereafter, Dionysius Areopagite, who became the first bishop of the city, converted to Christianity, as did Damaris, the first Athenian woman to do so. She was subsequently martyred for her faith.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

Situated to the north-west of the Acropolis, the ancient Agora of Athens was originally established as the administrative and trade center of the city, thus its name, the Agora, the “trade marketplace.” Deep in antiquity, the agora witnessed the procession of Panathinaia, the greatest celebration in the ancient city of Athens, one memorializing the unification of all of Attica under King Theseus.

Situated to the north-west of the Acropolis, the ancient Agora of Athens was originally established as the administrative and trade center of the city, thus its name, the Agora, the “trade marketplace.” Deep in antiquity, the agora witnessed the procession of Panathinaia, the greatest celebration in the ancient city of Athens, one memorializing the unification of all of Attica under King Theseus.

Video by fabdrone

Inhabited since the pre-historic era, the Agora had become the city center by the 6th Century B.C., and was home to a plethora of secular and sacred social activities, practiced in a multitude of public buildings, many of which still stand in ruins today. Throughout its turbulent history, the Agora survivied multiple sacks, suffering its most serious damage from the Persians in 480 B.C., the Romans under Syllas in 86 B.C., and the Heruli in 267 A.C. Finally abandoned in the 6th century, the area was dug under, eventually being covered over by houses and churches. The ruins of the ancient Agora remained buried and forgotten for fourteen-hundred years, until extensive excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries revealed its archaeological treasures.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

Academia Platonos, is an Athenian neighbourhood that has experienced intense industrial and residential development. Its name derives from two sources, the most recognizable being the famous Athenian philosopher, Plato, the second being a local Greek hero by the name of Akademos. Founded by Plato in 387 B.C., the Academy thrived during the years of the Neo-Platonic philosophers, until being permanently closed in 529 B.C., by Emperor Justinian, who shut down all other Athenian schools as well.

Inhabited since the early pre-historic era, this area began undergoing major changes with the arrival of Tyrant Hippias in the 6th Century B.C. A gymnasium was built on the site, and Hippias built a peribolo; nearly a century later, Cimon planted the entire area with trees, but in 86 B.C. they were chopped down when Syllas sacked Athens. Excavations over the last eighty-three years have revealed some truly significant findings here, such as an arched residence from the Early Helladic era, thought to be the actual home of the mythical hero, Akademos; a sacred house from the Geometric era; a peristyle building from the 4th century B.C.; the Roman gymnasium dating to the 1st century A.C., and multiple other buildings.

Inhabited since the early pre-historic era, this area began undergoing major changes with the arrival of Tyrant Hippias in the 6th Century B.C. A gymnasium was built on the site, and Hippias built a peribolo; nearly a century later, Cimon planted the entire area with trees, but in 86 B.C. they were chopped down when Syllas sacked Athens. Excavations over the last eighty-three years have revealed some truly significant findings here, such as an arched residence from the Early Helladic era, thought to be the actual home of the mythical hero, Akademos; a sacred house from the Geometric era; a peristyle building from the 4th century B.C.; the Roman gymnasium dating to the 1st century A.C., and multiple other buildings.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

From its perch atop a pine-covered hill on the island of Aegina, the imposing temple of the Afaia watches over the sea. Built in the early 6th Century to replace an earlier Doric temple, this well preserved structure, located on the northeast side of the island, is dedicated to Afaia, a deity related to the Cretin goddess, Britomartis-Diktynna.

From its perch atop a pine-covered hill on the island of Aegina, the imposing temple of the Afaia watches over the sea. Built in the early 6th Century to replace an earlier Doric temple, this well preserved structure, located on the northeast side of the island, is dedicated to Afaia, a deity related to the Cretin goddess, Britomartis-Diktynna.

The original, Doric-style structure was built from local limestone, with a double internal colonnade and a pitched roof with tiles made of Parian marble.

Its gables are now on exhibit at the Munich Sculpture Gallery. Made of marble, they depict themes from the Trojan War, featuring local heroes, like Telamon, son of Eakos. The western gable is archaic, dating from the late 6th Century B.C., while the eastern gable features more recent, classical elements from the early 5th Century B.C. Ancient tradition has it that the Temple of the Aphaia, along with the Acropolis and the Temple of Sounion, align to form a triangle.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

The majestic Temples of Poseidon and Athena stand on the rock of Cape Sounion, at the southern tip of the Attica peninsula, their sheer size and beauty causes admiration, whether viewed by sea or land. Used by the Athenians as a place of worship, as well as a fortress guarding the commercial seaways of the Aegean Sea, the Temple of Poseidon could be seen from afar by ships approaching the cape.

The majestic Temples of Poseidon and Athena stand on the rock of Cape Sounion, at the southern tip of the Attica peninsula, their sheer size and beauty causes admiration, whether viewed by sea or land. Used by the Athenians as a place of worship, as well as a fortress guarding the commercial seaways of the Aegean Sea, the Temple of Poseidon could be seen from afar by ships approaching the cape.

According to the ancient Greek mythology, King Egeas committed suicide here, leaping to his death after seeing the ominous black sails of his ships returning home from Crete. Cape Sounion is one of the most photographed landscapes in Greece, and the view from the site is exquisite, day or night, but especially in the evening during a full moon. The monument attracts millions of Greek and foreign visitors.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

One of the most important archaeological sites in Greece, Eleusis graphically displays the vast history of this residential area. Inhabited since the Middle Helladic era, it is renowned for the Eleusinian Mysteries, and Aeschylus, greatest of the tragic poets. As far back in time as ancient Mycenae, the destiny of Eleusis has been linked to Athens.

A number of major monuments occupy this site, including: The Sacred Yard, the ancient area of gathering of the believers, and the outmost destination of the Sacred Road; the Great Propylaea, its Doric order entrance, a replication of the Mnisseclean Propylaea of the Acropolis in Athens; the Small Propylaea, displaying an Ionic order entrance; the Telesterion, site of the Palace and worship of adytum; the Triumphant Arches, Roman copies of the Arch of Hadrian in Athens; the Kallichoron Well, where, according to myth, Demeter sat during her quest for Persephone; the Ploutonion, a sacred cave with an entrance to Hades; and the Mycenaean manor, a rectangular Mycenaean temple.

A number of major monuments occupy this site, including: The Sacred Yard, the ancient area of gathering of the believers, and the outmost destination of the Sacred Road; the Great Propylaea, its Doric order entrance, a replication of the Mnisseclean Propylaea of the Acropolis in Athens; the Small Propylaea, displaying an Ionic order entrance; the Telesterion, site of the Palace and worship of adytum; the Triumphant Arches, Roman copies of the Arch of Hadrian in Athens; the Kallichoron Well, where, according to myth, Demeter sat during her quest for Persephone; the Ploutonion, a sacred cave with an entrance to Hades; and the Mycenaean manor, a rectangular Mycenaean temple.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

To date, the theatre at Thoricus is the oldest known theatre in existence. Located north of Lavrion, almost adjacent to the city, it dates to the end of the Archaic era, between 525 and 480 B.C. But that is not its only distinction. Unlike Greek theatres built in later eras, it is elliptical rather than circular in shape, and has a rectangular, rather than circular orchestra. With 21 rows of seats, the theatre had a seating capacity of 4,000 people. On the east side of the orchestra, sculpted out of the natural rock, is the base of the ancient temple, and a room, complete with benches, also sculpted from the rock.

Dating from the mid-5th Century, the temple was used for meetings of the Demos’ authorities, and, like the small temple and room complex of Dionysus, it also served the theatre when it was in operation; It had a wooden scene, which, unlike later theatres, was never replaced with one made of stone. The area of the theatre was never intended solely for theatrical performances, but was also used for meetings of the citizens of Thoricus.

Dating from the mid-5th Century, the temple was used for meetings of the Demos’ authorities, and, like the small temple and room complex of Dionysus, it also served the theatre when it was in operation; It had a wooden scene, which, unlike later theatres, was never replaced with one made of stone. The area of the theatre was never intended solely for theatrical performances, but was also used for meetings of the citizens of Thoricus.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

Located at the end of Ermou street, the Kerameikos Archaeological site is one of the major archaeological sites in Athens. And though only a small portion of this ancient city quarter is open to the public, this site, home to the “Kerameis” (the potters) of antiquity, is a powerful and moving glimpse into the distant past. Also standing here are the ruins of the Dipylon Gate, the imposing double gates of the Themistocleian city wall, circa 478 B.C. Numerous tombs with “replicated anaglyphs” occupy the site as well, the original anaglyphs being safely preserved in the Kerameikos Museum, also located here.

The notorious Demosion Sima, the public graveyard where ancient Athenians once buried their war heroes, is also part of this intriguing site. It is believed that Kerameikos took its name from one of two sources: the ancient Kerameis, potters whose workshops occupied the area, or from the name of the Greek hero, Keramos. The imposing gates were first brought down by Syllas during his conquest of Athens in 86 B.C., and the final destruction took place during the Herulian sack of Athens in 267 A.C. Thereafter, the area was used as a graveyard until the end of the Roman era in the 6th century.

The notorious Demosion Sima, the public graveyard where ancient Athenians once buried their war heroes, is also part of this intriguing site. It is believed that Kerameikos took its name from one of two sources: the ancient Kerameis, potters whose workshops occupied the area, or from the name of the Greek hero, Keramos. The imposing gates were first brought down by Syllas during his conquest of Athens in 86 B.C., and the final destruction took place during the Herulian sack of Athens in 267 A.C. Thereafter, the area was used as a graveyard until the end of the Roman era in the 6th century.

Source: www.athensattica.gr