On the south of Mycenae, on the slopes of the hill called Aetovouno or Euboea, built on three hills, lies the Heraion, a very important temple dedicated to Hera. It was in this temple that every two years following every Olympiad the panhellenic ancient festival of Heraia took place. This magnificent sanctuary, flourished from the 5th century B.C until the Roman age and it consisted of the official religious center of the region of Argos. Apart from the Heraion the site has ruins of Roman baths and other buildings.

The Heraion is located between the archeological site of Mycenae and the city of Argos, on the slopes of the mountain called Aetovouno or Euboea. It was a place of worship dedicated to Hera, protector of Argos. This imposing temple was built in the 8th century B.C. In the early 7th century it was the official religious center of the region of Argos and it flourished from the 5th century B.C. until the Roman period. According to the tradition it was created by the hero Argos or Phoroneas, son of Inachus.

The Heraion consists of three levels. During the first centuries of its use, the place of worship was situated on the upper level and it was protected by a cyclopean wall. During the 6th century B.C two Doric style stoas were constructed on the south of the middle terrace. In 423 B.C., though, the first temple burned down and a second temple was built by Eupolemos. This second temple was constructed on the middle terrace between the “west building” hosting the symposiums and the “east building”.

The Heraion consists of three levels. During the first centuries of its use, the place of worship was situated on the upper level and it was protected by a cyclopean wall. During the 6th century B.C two Doric style stoas were constructed on the south of the middle terrace. In 423 B.C., though, the first temple burned down and a second temple was built by Eupolemos. This second temple was constructed on the middle terrace between the “west building” hosting the symposiums and the “east building”.

In this temple was the chryselephantine statue of Hera, a work of Polykleitos, a wooden statue of the goddess taken from Tiryntha and a chryselephantine statue of Eve created by Naukides. There were other statues representing heroes of the region and priestesses of Hera at the Propylaea (entrance) of the temple. The sack of Troy and the birth of Zeus were depicted on the impressive pediments, parts of which are exposed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

It was in this temple that every second year after each Olympiad the Heraia or Hekatombaia were celebrated, a festival in honor of the goddess and one of the biggest festivals in Argos. Apart from the festival, games also took place, and the winners were awarded coppery objects. The existence of this festival is documented by Herodotus when he recounts the sacrifice of two brothers, Kleobis and Biton who dragged the cart of their mother, the priestess of Hera Argeia, while the oxen assigned to the task were used for another work.

All the priestesses of the temple had a lifelong service and were highly appreciated by the people of Argos. The importance of the sanctuary is also attested to by the fact that the calculation of the local date was based on the year the service was assigned to each priestess and on the offerings of Nero and Hadrian. Catharsis ceremonies took place in the temple, in the water of river Eleftherios. The excavations brought to light an Apollo temple, Roman baths, a cemetery and the Heraion.

Source: www.mythicalpeloponnese.gr

Τhe Mycenaean acropolis of Midea, the third fortified acropolis of Argolida, is related to many myths. It played the role of a craft industry, administrative, military and financial force. It was built on a hill and, according to findings dating to the 13th century, it was inhabited since the prehistoric age. The “cyclopean wall” and the two gates, one on the east and one on the west, protect a 24.000m² region. The huge tunnel, the bastion and a number of houses with fine frescos fascinate the visitor. Furthermore the wealth and the glory of the acropolis are documented by the numerous archaeological findings. Their study greatly contributed to the decoding of the script Linear B demonstrating the continuity of the Greek language.

Between Mycenae and Tiryns, built on a 2.70m high ancient hill, rises the third most important acropolis of Argolida, the Mycenaean acropolis of Midea. According to the legend this land has been founded by king Perseus and consists of Alkmini’s, Hercules’ mother’s, homeland. Another legend states that this land was the prison where Hippodamia, Pelops’ mother, was punished, and the land was named after the queen. It was built to control the ancient passage to Epidaurus. Greek and foreign researchers have underlined its strategic position; the acropolis controls the plain of Argolida.

Between Mycenae and Tiryns, built on a 2.70m high ancient hill, rises the third most important acropolis of Argolida, the Mycenaean acropolis of Midea. According to the legend this land has been founded by king Perseus and consists of Alkmini’s, Hercules’ mother’s, homeland. Another legend states that this land was the prison where Hippodamia, Pelops’ mother, was punished, and the land was named after the queen. It was built to control the ancient passage to Epidaurus. Greek and foreign researchers have underlined its strategic position; the acropolis controls the plain of Argolida.

For many centuries, it constituted an important industial, administrative, military and financial centre. This is documented by the numerous findings brought to light by the excavations carried out in 1939.

The ceramic findings of the late Helladic period indicate that the ancient hill was inhabited from the prehistoric age. The “cyclopean walls” surround the hill and protect a 24.000m² region, controlling the upper acropolis and the lower sections of the hill with its constructions. One side of the hill is steep consisting thus of a natural fortress and inaccessible barrier for the enemies. Two gates built with natural limestone, on the eastern and the western side, complete the fortification. An underground megalithic tunnel documents that there was a developed water and drainage system and it demonstrates a specific and detailed architectural design, as it resembles the respective constructions of Tiryns.

A powerful earthquake and the subsequent fire put an end to the Mycenaean Midea. This was documented by the skeleton of a girl, found at the eastern gate, covered by huge stones. The buildings had been repaired and reused in the 12th century BC.

At the western gate, a bastion, an outpost and a number of houses were uncovered. Pieces of the walls revealed that they had a fine decoration. The findings of semi-precious stones, ceramic and stone tools, armours and gold jewellery moulds document that the buildings were used as storage rooms and laboratories, proving Mideas’ industrial strength. One of the most important findings, the large rare idol on wheels depicting a goddess, revealed the religious practices of this period. Seals and inscribed jars contributed to the decoding of the Linear B, documenting the historical unity and continuity of the Greek language.

Source: www.mythicalpeloponnese.gr

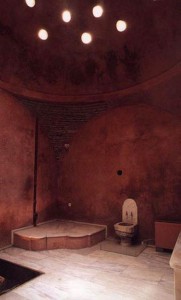

The Turkish bath of the Aerides is located on Kyrristou street in Plaka. Built during the years of the Ottoman occupation, the “Ibn Efendi Turkish Bath” was open to the public. Extensively damaged during the siege of the Acropolis by Kioutahi Pasha in 1827, it was later repaired and modernized by King Otto. Following World War II, the bath continued operations until 1960, when it was abandoned.

The Turkish bath of the Aerides is located on Kyrristou street in Plaka. Built during the years of the Ottoman occupation, the “Ibn Efendi Turkish Bath” was open to the public. Extensively damaged during the siege of the Acropolis by Kioutahi Pasha in 1827, it was later repaired and modernized by King Otto. Following World War II, the bath continued operations until 1960, when it was abandoned.

During the 1980’s and the 1990’s, the Ministry of Civilization performed several interventions and restructuring work, in order to restore the building and turn it into an exhibition venue. Today, visitors can see how a Turkish bath operated during the time of the Ottoman occupation, as well as subsequent eras. The building also houses an annex of the Museum of Hellenic Folk Art.

During the 1980’s and the 1990’s, the Ministry of Civilization performed several interventions and restructuring work, in order to restore the building and turn it into an exhibition venue. Today, visitors can see how a Turkish bath operated during the time of the Ottoman occupation, as well as subsequent eras. The building also houses an annex of the Museum of Hellenic Folk Art.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

Excavations carried out during the previous century, north of the modern town of Sparta, brought to light an impressive construction. The edifice that dates back to the 5th century B.C. was made from large limestone. Waldstein, who carried out the excavations in 1892, initially thought it was a small temple. Although its use is not yet verified, it is believed to be the tomb of Leonidas. According to Pausanias, it was here that the remains of the legendary king of Sparta were transferred and buried after the battle in Thermopylae. The tomb of Leonidas is the only preserved monument of the Ancient Agora.

The tomb of Leonidas, north to the modern town of Sparta, is an emblem and an important monument, as it is the only monument preserved from the Ancient Agora. Also known and as Leonidaion, excavations of the construction were carried out by Waldstein in 1892. The impressive edifice (12.5 × 8.30 m) has the form of a temple probably dating back to the late 5th century B.C.. It was made of massive limestone and its interior was divided in two connected chambers. The eastern chamber was 3.15 meters long, had the form of a vestibule and was ornate with columns.

The tomb of Leonidas, north to the modern town of Sparta, is an emblem and an important monument, as it is the only monument preserved from the Ancient Agora. Also known and as Leonidaion, excavations of the construction were carried out by Waldstein in 1892. The impressive edifice (12.5 × 8.30 m) has the form of a temple probably dating back to the late 5th century B.C.. It was made of massive limestone and its interior was divided in two connected chambers. The eastern chamber was 3.15 meters long, had the form of a vestibule and was ornate with columns.

Until today, it is not known what the edifice was used for. It is believed to be a cenotaph, while many researchers share the opinion that it is the temple of Karneio Apollo. Although there is no indication on the correlation between the temple and the legendary king of Sparta, according to local tradition and the travel writer Pausanias, the remains of Leonidas were transferred and buried there. It is because of this, that the locals believe it to be the tomb of Leonidas. According to Pausanias the tomb was situated to the west of the Agora, opposite to the theater, and hosted games once a year.

Source: www.mythicalpeloponnese.gr

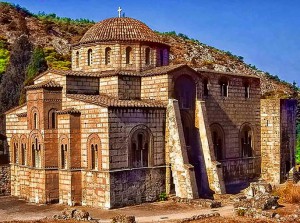

The byzantine church of Kapnikarea is one of the major landmarks of Athens’ Byzantine past. Dating from the 11th century, it is dedicated to the “Presentation of the Virgin to the Temple,” and lies in the middle of Ermou street. It is believed that the church was built over an older, Christian temple, commissioned in the 5th Century A.C. by the Athenian Empress of Byzantine, Eudokia, wife of Emperor Theodosius the Younger. Constructed atop the foundations of the ancient temple of Athena or, perhaps, Demeter, it is today owned by the University of Athens.

The byzantine church of Kapnikarea is one of the major landmarks of Athens’ Byzantine past. Dating from the 11th century, it is dedicated to the “Presentation of the Virgin to the Temple,” and lies in the middle of Ermou street. It is believed that the church was built over an older, Christian temple, commissioned in the 5th Century A.C. by the Athenian Empress of Byzantine, Eudokia, wife of Emperor Theodosius the Younger. Constructed atop the foundations of the ancient temple of Athena or, perhaps, Demeter, it is today owned by the University of Athens.

Constructed as a domed, cross-in-square complex, the three sections of the church were built at separate times; In the early 20th Century, the chapel of St. Barbara was added to the northern section of the church. Many of the interior murals were painted by famed artist, Fotis Kondoglou. The temple owes its name to its first owner who, according to tradition, collected the “Tobacco Tax” (kapnikos foros) in the city. Yet another tradition is connected to the church’s older name, “Kamouharea,” the famous silk cloth workshops (kamouhades) that operated in the area.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

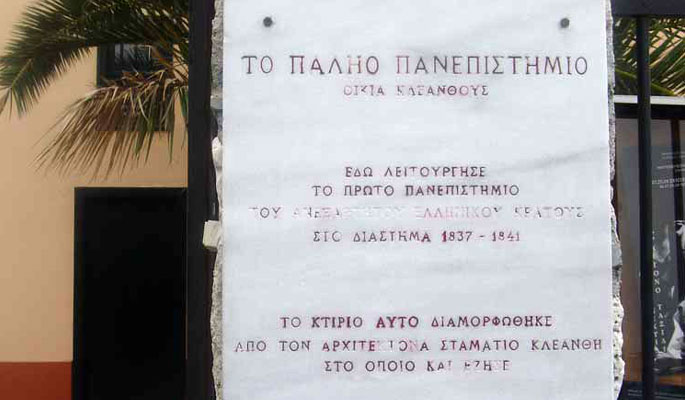

Kleanthi-Schaubert, or the “Old University,” is on Tholou street in one of the higher sections of Plaka. Built around the 17th Century, the institution was purchased from its Ottoman owner by two close friends, architects Kleanthis and Schaubert, who, after arriving in the newly liberated Athens, went to work on the old building, repairing and restoring its huge walls and domed basements, adding other buildings, and uniting them all into a single complex. In 1834 the building housed the Girls High School and, later, the newly founded University.

Kleanthi-Schaubert, or the “Old University,” is on Tholou street in one of the higher sections of Plaka. Built around the 17th Century, the institution was purchased from its Ottoman owner by two close friends, architects Kleanthis and Schaubert, who, after arriving in the newly liberated Athens, went to work on the old building, repairing and restoring its huge walls and domed basements, adding other buildings, and uniting them all into a single complex. In 1834 the building housed the Girls High School and, later, the newly founded University.

Then, in 1837, three new rooms and an Anatomy auditorium were added to cover the needs of the new University. When the University finally moved into its own building after 1841, the original Kleanthi Residence became the Didaskaleion and the Experimental InterTeaching School, which was later used as a barracks. The facility changed hands many times over the years, and was used for various purposes until 1963 when it was declared a listed building. In 1967 it was officially assigned to the University. Since then it has been restored, and now houses the University’s History Museum.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

The 17th century Church of Agioi Anargyroi, also known as the Metochion of the Holy Sepulchre, is located at the Anafiotika, in Plaka. Originally opened as a convent, presumed to have been owned by the prominent Kolokinthi family.

The church is a single-clite basilica, dedicated to the Ag. Anargyroi. Due to its function as an embassy church of the Holy Sepulchre since the 18th century, the Metochion is deeply involved with the holy ceremonies of Easter. Designated as the point of initial reception of the Holy Light from the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, on the night of celebration of the Holy Resurrection, the church attracts many visitors. It was built on the site of an ancient temple dedicated to goddess Aphrodite.

The church is a single-clite basilica, dedicated to the Ag. Anargyroi. Due to its function as an embassy church of the Holy Sepulchre since the 18th century, the Metochion is deeply involved with the holy ceremonies of Easter. Designated as the point of initial reception of the Holy Light from the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, on the night of celebration of the Holy Resurrection, the church attracts many visitors. It was built on the site of an ancient temple dedicated to goddess Aphrodite.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

The church of Agios Nikolaos Ragavas is located in Plaka, close to the Anafiotika neighborhood. Built in the 11th century, it is one of the major monuments from that era. Based on the simple four-aisled, cross-in-square design, the church is topped with a small octagonal dome of the Athenian era. Originally belonging to a Byzantine family named Ragavis.

The church of Agios Nikolaos Ragavas is located in Plaka, close to the Anafiotika neighborhood. Built in the 11th century, it is one of the major monuments from that era. Based on the simple four-aisled, cross-in-square design, the church is topped with a small octagonal dome of the Athenian era. Originally belonging to a Byzantine family named Ragavis.

The church became derelict during the Revolution of 1821, but was eventually rebuilt using the original materials. Since then, it has undergone numerous modifications, which have significantly altered its appearance. During the 1970’s it was partially restored to its original condition, but not completely. Tradition has it that this church’s bell was the first one to ring out following the liberation of Athens from German occupation on October 12, 1944.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

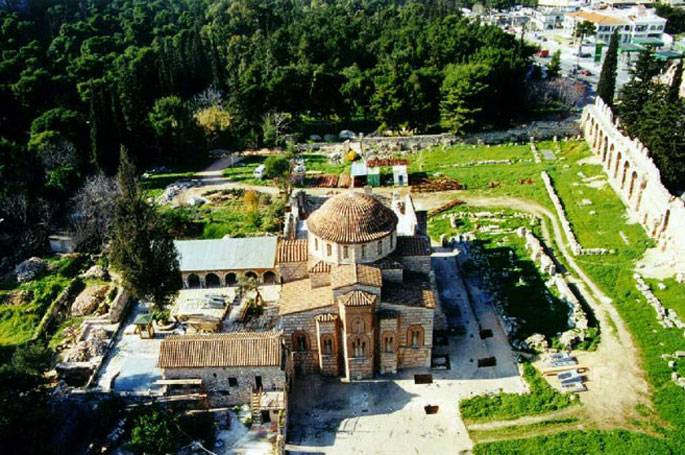

Situated at the edge of the Haidari parkland, the Dafni Monastery is said to have been built at the site of the ancient temple of Apollo Dafnaios. Fortified and surrounded by high defensive walls, only two entrances lead to the perivolos, where the Monastery’s main church is located, the imposing “Katholikon.”

Situated at the edge of the Haidari parkland, the Dafni Monastery is said to have been built at the site of the ancient temple of Apollo Dafnaios. Fortified and surrounded by high defensive walls, only two entrances lead to the perivolos, where the Monastery’s main church is located, the imposing “Katholikon.”

Other structures, including the monks’ chambers and the dining room, are also located here. Like most of Athens’ Byzantine buildings, the monastery’s Katholikon dates from the 11th Century, and has been restored multiple times during its thousand years of existence. Fortunately, many of its exquisite, original mosaic decorations have been preserved.

Over the centuries, the Monastery gradually fell into disrepair and, by the late 19th Century, it had been abandoned by the monks, subsequently being used as a public mental hospital. Today, however, this fortified monastery is included in the Unesco World Record of Cultural Heritage.

Source: www.athensattica.gr

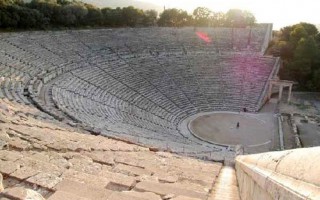

The Herod Atticus Odeon, or the Irodeion as it is called today, was built on the south-western slope of the rock of the Acropolis during the Roman era, by the Athenian magnate Herod Atticus, in memory of his wife Regilla. Following the city’s decline during the Byzantine era, the Odeon became a derelict and was buried under tons of dirt. During the subsequent Ottoman occupation, foreign visitors to the site gave the scant remnants many different names, most of them made up. It seemed as if the Irodeion would simply fade from memory.

The Herod Atticus Odeon, or the Irodeion as it is called today, was built on the south-western slope of the rock of the Acropolis during the Roman era, by the Athenian magnate Herod Atticus, in memory of his wife Regilla. Following the city’s decline during the Byzantine era, the Odeon became a derelict and was buried under tons of dirt. During the subsequent Ottoman occupation, foreign visitors to the site gave the scant remnants many different names, most of them made up. It seemed as if the Irodeion would simply fade from memory.

That is, until 1764, when British archaeologist, Chandler, reawakened interest in Herod Atticus Odeon. Then, in the 19th Century, excavations unearthed the ruins of the ancient theatre. Completely refurbished by the 1950s, the seats were now covered with Pentelic marble, and the orchestra with marble from Mt Hymettus. Since then the theatre has been used for high-level cultural productions during the summer season, mainly the Athens Festival.

Source: www.athensattica.gr